Ever since humans became sedentary, the land and the water have been the main causes of conflict.

Ever since humans became sedentary, the land and the water have been the main causes of conflict.

The bloodiest wars have been fought over a bigger or smaller share of land. Life and Water seem to pair up as synonyms throughout history. From that first primordial soup to the first non-nomadic peoples that settled down in areas near water courses. Modern water distribution nets seemed to have put it behind in importance, but environmentalist prophecies have put water back in its prominent place, due to its potential future shortage.

Accordingly, many regulations have been enacted in connection with its use and ownership. In Argentina, the Civil Code, which deals with the relationships among persons, property, inheritance, obligations and contracts, establishes in Section 2340 that navigable rivers and lakes shall be considered public property. This means that they may be used by all inhabitants in general and that they are intended to be accessed, used and enjoyed by each one of them. Public property cannot be bought, sold or transferred.

Accordingly, many regulations have been enacted in connection with its use and ownership. In Argentina, the Civil Code, which deals with the relationships among persons, property, inheritance, obligations and contracts, establishes in Section 2340 that navigable rivers and lakes shall be considered public property. This means that they may be used by all inhabitants in general and that they are intended to be accessed, used and enjoyed by each one of them. Public property cannot be bought, sold or transferred.

The phenomenon of latifundia seems to continue beyond the Middle Ages. Anachronistic and shameless, the Argentinian reality evidences that lands are increasingly concentrating in fewer and fewer hands: 43% of the territory is owned by 1.3% of owners, according to the 2002 National Farming Census.

And the problem that arises, set aside ideological discussions, is that in those huge estates are located rivers and lakes. This is supposed to be easily solved by Section 2639 of the above mentioned Code, which states that “landlords whose properties border rivers or channels that serve to communication by water shall allow a 35-meter street or public road leading to the edge of the river or channel, subject to no right to compensation”.

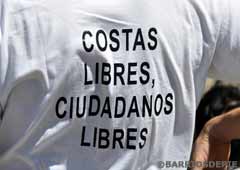

However, as it often happens in this part of the world, theory is quite far from practice and there are many complaints about the failure to comply with the obligation of free access to these lakes and rivers. Various neighbors and social organizations drive campaigns, make complaints, organize demonstrations and boycotts, and the Internet is full of articles and texts that put words to these actions.

Douglas Tompkins, who owns several hectares in Patagonia and Iberá Wetlands, in the province of Corrientes, is one of the accused. A scandal is also brewing about two properties owned by Ted Turner –founder of CNN and former Vice President of AOL Time Warner-: the estancia La Primavera, located inside Nahuel Huapi National Park, and the estancia Collón Cura.

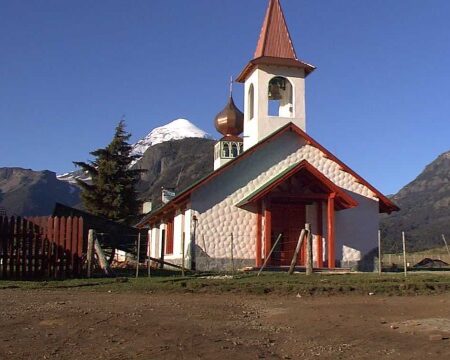

In the case of the estancia La Primavera, of about 5,000 hectares, neighbors and fishermen have submitted several formal complaints about staff from the estancia mistreating them when they were trying to access Minero River, Traful River, or Traful Lake, and about their inability to access them.

In the case of the estancia La Primavera, of about 5,000 hectares, neighbors and fishermen have submitted several formal complaints about staff from the estancia mistreating them when they were trying to access Minero River, Traful River, or Traful Lake, and about their inability to access them.

The estancia Collón Cura does not fall behind. The complaints are the same: mistreatment, restricted access to the river and shores, armed guards…

Joseph Lewis’s 14,000-hectare property is also accumulating complaints. The main problem many neighbors report is the alleged restriction to access Lake Escondido through the property.

Another nerve center of conflict is the area of Lake Lolog, where some landlords have built walls and private piers. There, the memory of bloodshed is still fresh. Years ago, a group of three friends decided to camp and fish. They settled by the lake, near the sources of Quilquihue River. But something happened –to some, an obscure incident; to others, a crystal clear one- and one of the men, Cristian González, was shot dead by a forest ranger.

Today, the Cristian González Association for Free Access to Rivers and Lakes (Asociación por el libre acceso a las costas de ríos y lagos Cristian González) drives conscience-raising activities, organizes demonstrations and distributes material to inform about the laws and rights related to the cause that inspires them.